January 4, 2026

White Paper I

Abstract

Ex vivo culture of mammalian embryos has been explored for decades, with development in mice progressing to mid-gestation. Beyond this stage, current systems fail because they cannot replace the support normally provided by the placenta.

Here, we culture mouse embryos ex vivo and observe trophoblast invasion with organization consistent with early placental morphogenesis, including three-dimensional extension while a structured trophoblast layer is maintained.

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that key features of the placental invasive program can be activated in a fully controlled ex vivo system.

Main

Ex vivo culture of mammalian embryos is most commonly performed using roller culture systems (New, 1978). These approaches reliably support post-implantation development through organogenesis and have generated important biological insights. However, they ultimately fail as metabolic demands increase, largely because they lack a maternal–fetal interface capable of delivering sufficient oxygen and nutrients (Aguilera-Castrejón, 2021).

In parallel, significant progress has been made in supporting extremely premature infants using umbilical cannulation and pumpless extracorporeal oxygenation (Partridge et al., 2017). Although one could imagine bridging roller culture to such cannulation-based support,

the transition would likely be inefficient, difficult to reproduce, and impractical as a broadly useful research platform. Instead, a culture system that enables placental development ex vivo, together with an engineered analog of the maternal–fetal interface, would allow continuous, uninterrupted growth and open a new window for basic research, translational studies, and ultimately sustained ex vivo gestation. Moreover, achieving reproducible, long-term culture at scale will likely require multi-parameter closed-loop control capable of

sensing developmental state and dynamically adjusting the environment.

Recently, an ex vivo uterine model achieved an impressive recapitulation of implantation, including early trophoblast invasion (Hiraoka, 2025). However, this approach relies on dissected uterine tissue and primarily captures mural trophectoderm invasion, which does not progress to placenta formation. Other important work has demonstrated trophoblast invasion in synthetic environments, but again largely reflects outgrowth from mural trophectoderm rather than placenta-forming lineages (Govindasamy, 2021)

Here, we present a representative result from our system showing placental trophoblast invasion in culture. To our knowledge, this is the first report of deep, three-dimensional trophoblast invasion occurring in a mouse embryo culture system.

Results

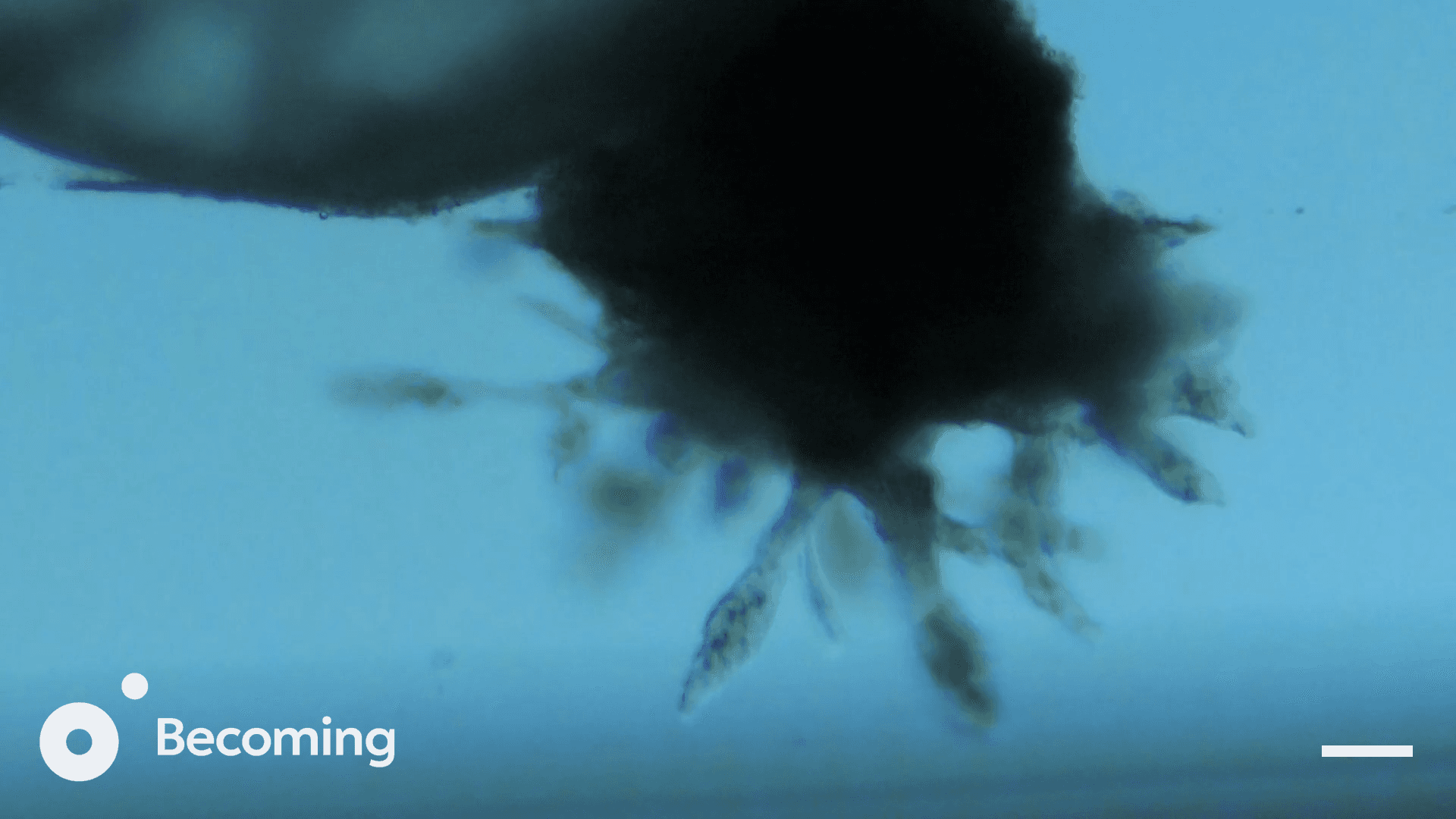

Mouse embryos were imaged in time-lapse from the lateral perspective, with the field of view centered on the ectoplacental cone (EPC). Over the course of culture, multiple branching protrusions emerged from the EPC and extended outward. These protrusions exhibited dynamic behaviors including growth, retraction, branching, fusion, and occasional

detachment into single migrating cells.

Video 1: Time-lapse imaging of invasive trophoblast protrusions emerging from the ectoplacental cone. The interval between is frame is 20 minutes. A 2hr 30 time gap is present in the sequence.

Figure 1a)

0 hrs

Figure 1b)

8 hrs

Figure 1c)

12 hrs

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrate invasion by trophoblasts emerging from the ectoplacental cone in a fully controlled ex vivo system. These cells normally initiate the earliest stages of placental formation. In our platform, they not only extend invasive protrusions but also express markers consistent with differentiated invasive trophoblast (data not shown), while an underlying epithelial trophoblast layer is maintained. Together, this suggests that key components of the placental invasive program, and early lineage organization, can become activated under ex vivo culture conditions. This represents a capability that has not previously been available in a reproducible culture system.

This result marks an inflection point for ex vivo development systems. Prior approaches have supported post-implantation growth but largely stalled once placental function became essential. By contrast, the invasion-like activity and lineage differentiation observed here indicate that the pathway toward an engineered placental interface can be initiated directly in culture. While this does not yet constitute a functional placenta, it represents a concrete step toward addressing what has been the principal bottleneck in extending development ex vivo.

Future work will involve deeper characterization of the invasive structures using molecular, mechanical, and functional assays. It will also involve systematic tuning of environmental parameters to control invasive behavior. In parallel, we will integrate controlled perfusion

systems that can progressively transition invasion into a perfused exchange layer. Ultimately, achieving closed-loop control over oxygenation, nutrients, hormones, and mechanical environment will be essential for stabilizing placental support over longer developmental windows.

While much remains to be engineered, the results presented here represent a meaningful step toward a platform capable of supporting the full trajectory of mammalian development ex vivo.

Ethics

All experiments were conducted with approval from an institutional IACUC committee.

Citations

New, D. A. T. (1978). Whole-embryo culture and the study of mammalian embryos during organogenesis. Biological Reviews, 53, 81-122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1978.tb00993.x

Partridge, E. A., Davey, M. G., Hornick, M. A., McGovern, P. E., Mejaddam, A. Y., Vrecenak, J. D., Mesas-Burgos, C., Olive, A., Caskey, R. C., Weiland, T. R., Han, J., Schupper, A. J., Connelly, J. T., Dysart, K. C., Rychik, J., Hedrick, H. L., Peranteau, W. H., & Flake, A. W. (2017). An extra-uterine system to physiologically support the extreme premature lamb. Nature Communications, 8(1), 15112. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15112

Aguilera-Castrejon, A., Oldak, B., Shani, T., Ghanem, N., Itzkovich, C., Slomovich, S., Tarazi, S., Bayerl, J., Chugaeva, V., Ayyash, M., Ashouokhi, S., Sheban, D., Livnat, N., Lasman, L., Viukov, S., Zerbib, M., Addadi, Y., Rais, Y., Cheng, S., Stelzer, Y., Keren-Shaul, H., Shlomo, R., Massarwa, R., Novershtern, N., Maza, I., & Hanna, J. H. (2021). Ex utero mouse embryogenesis from pre-gastrulation to late organogenesis. Nature, 593(7857), 119-124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03416-3

Hiraoka, T., Aikawa, S., Mashiko, D., Nakagawa, T., Shirai, H., Hirota, Y., Kimura, H., & Ikawa, M. (2025). An ex vivo uterine system captures implantation, embryogenesis, and trophoblast invasion via maternal-embryonic signaling. Nature Communications, 16(1),

5755. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60610-x

Govindasamy, N., Long, H., Jeong, H.-W., Raman, R., Özcifci, B., Probst, S., Arnold, S. J., Riehemann, K., Ranga, A., Adams, R. H., Trappmann, B., & Bedzhov, I. (2021). 3D biomimetic platform reveals the first interactions of the embryo and the maternal blood vessels. Developmental Cell, 56(23), 3276-3287.8.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2021.10.014